It’s London Craft Week this week so we’re busy sharing our love and expertise in the craft of shoemaking all week over on Instagram.

And as shoemakers are a rarity here in the UK (shoemaking is considered an endangered craft) we're super lucky to have our very own shoemaker Thomas Murphy on the team here at CHAPTER 2 so we thought it was about time you got to meet the maker:

Tell us how you became a shoemaker…

When Fay and I started college in the late 90s at Cordwainers in London our tutors were made up of people who’d worked in different factories in East London, Northampton or Leicester. At that point there was very little industry left and what little there was was coming to an end and as a result of that there wasn’t a lot of positivity around the shoemaking industry in this country.

At the time not many fashion designers even made shoes. Shoes and accessories weren’t a big part of their business back then so we were basically told it was a dying industry. Which isn’t that inspiring after you’ve just moved to Hackney which at the time was an ‘interesting’ place to live and a bit dangerous really. About 25 of us had moved from all round the country to London to do a shoemaking & design degree and be told that the industry was dying wasn’t really what we wanted to hear when we first arrived there.

However, doing that degree did give me an insight into the different aspects of shoe design and shoemaking was one part of that. I wouldn’t say at the end of it that I was a shoemaker. I could make a shoe, not a very good shoe. I definitely wasn’t at a standard where I could sell a shoe I’d made, no where near really. In fact I couldn’t even thread the sewing machine when I left college.

Then I went and hung about with other people making handmade shoes and one of those guys also told me there’s no money in handmade shoes which I guess was true to a point at the time. So then I started hanging out in some of the small shoes factories that were left in Leyton & Bow and I started to pick up stuff from people working there.

Each shoemaker has their own speciality or niche within the world of shoemaking, what’s yours?

I suppose my speciality is making women's heels. I guess I was most interested in women's shoes when I was studying and then as I wanted to start my own label I realised that there wasn't much of a women's shoemaking industry left in this country. There’s still industry in Northampton making men's welted shoes but I wasn't so interested in that.

So, I worked with a few of the small factories left around East London. I worked with one in Bow who at the time were making Vivian Westwood shoes and some other kinds of small independent labels. They made Olivia Morris's shoes and they did different stuff for fashion shows around that time like Boudicca and Kim Jones. I went along there and started to make shoes with them.

A guy who made really interesting heels called Paul Murray Watson who did some work for different fashion designers at the time including Robert Cary Williams and Boudicca introduced me to John at Amathus and I started to make some shoes with John under my own label. I guess one of the things I think I did differently to other people was because I wasn't living in London at the time I used to stay there while they were doing the work on my shoes so I'd watch them lasting the shoes or I'd sit with the closer Tom and watch how he did the closing. I'm someone who learns by watching and I guess I'd go away and then later on, years later, I'd start doing it myself. That was really my introduction to the world of women's heels, the kind of processes involved and the kind of specific techniques.

I guess when I think about it what's the difference between women's and men's shoes for me it's the fineness, it’s almost more delicate when you're making and for me you know, I'm not the best at making men's shoes.

If I make a men's shoe, it probably looks slightly more delicate than most men's shoe makers would make it. And then often I see women's shoes, and you can tell they've been made by someone who's used to making men's shoes because they're a bit heavier than I would make them. So it’s like fine nuanced techniques in the making,

Things which make a big difference can be the size of the thread that I used to sew the shoes together, the size of the needle, the weight of the lining, the kind of skive on the top line, everything adds up to a more delicate shoe. Of course the heels are another element which for me are another chance to be creative. With women’s it’s generally not a kind of low stack like you might see on a mens shoe, it gives more freedom to do something creative with the heel shapes.

Which part of the making process do you enjoy the most?

This is a difficult one because I think I enjoy different parts the process depending on how I’m feeling and at the moment I do everything. I do the pattern making, the closing and I do the actual making of the shoe.

At different stages of my career I’ve done only the pattern making and the clicking (cutting the leather) and someone else has done the closing (sewing) and making then I started to do more of the making alongside someone else I was working with. The most recent skill I’ve developed is closing. Each time I’ve developed a skill it’s really by necessity because there wasn’t any one else to do it.

Originally I enjoyed pattern making as it allowed me to get the style lines on the shoe how I wanted. So rather than draw a picture and give it to someone else and have their interpretation of my sketch being able to draw onto he last and make it into patterns enabled me to get to a place where I was happier with a style quicker. It eliminated the need to go back and forwards with someone else. And it enabled me to develop my understanding of pattern making, through trial and error really; making shoes, seeing how they fit, changing the lines,

At college I was taught a whole set of what felt like mathematical equations of how to make standard patterns for shoes. Once I understood the classical way, the principals of where different points need to be on shoes then I could start to be more creative, try different designs and move away from some of the more traditional shoe designs.

I’ve always done bits and pieces of making but I wasn’t that confident at making initially and that’s taken time to develop, again through watching other people’s technique. Much of my making has been what I call batch production so I’ve been making maybe 10 or 25 of something up to 100 of a similar type of shoe. Lots of the places I’ve worked or the people I’ve worked with were paid on piece work so they get paid a certain amount for each shoe they make, which meant they were interested in making them as quickly as they could. So I pick up different techniques from different people.

Some people I know when making softer women’s shoes didn’t use any nails at all, they’d use a lot of glue and that would be the way they’d make shoes. It would be all about how they could get it made quicker, make more money and basically get paid and then the same in closing. That was certainly all on piece work as well so it’s about speed. I’d sit with different closers and I’d watch their techniques, some better than others, and I’d take different bits from each one and then try and practise those myself.

I came to closing most recently of all the processes in shoemaking, again because there was no one else who could do it. No one else could do it the way I wanted to do it so I got myself a good machine and I sat on it and I practised for hours and hours and I guess I had the tenacity to keep going because it can be frustrating. Different leather skives differently, it stitches differently, the thread sits on it in a different way. You might need to treat it in a different way to put backers on so there’s a lot to learn even within closing.

And then if you’re doing the making too you start to understand if I make the shoe too fine and I pull it the stitching’s gonna split. It’s all a balance really of trying to make it strong enough that it’s going to last a long time when you wear it and not lose it’s shape and not so hard that its uncomfortable, and not too thin so it’s got weaknesses in.

I think at the moment I enjoy closing the most. It’s like doing a puzzle where in theory all the bits fit together but sometimes you have to adapt the pieces a little bit as you go along and it can look ok but then you don’t find out if you’ve done it well enough until you start lasting the shoe. That’s where you maybe find out there are bits you maybe need to refine.

After more than 20 years as a maker are there skills within shoemaking that you’d still like to learn?

I think if I had the time I’d probably spend more time learning traditional hand sewn techniques, the kind you might have on a bespoke men’s shoe. That’s something I periodically get more or less interested in depending on what I’m doing. I guess I’d also like to understand a little bit more about last making as I sometimes make lasts and it’s something I’m keen to develop as well.

I can essentially do all the processes myself which enables me to be autonomous which I enjoy. I can go into my workshop and make a pair of shoes without needing anyone else, which I guess has taken me 20 years to get to that point. But I wouldn’t say I’m excellent at hand sewing so I’d probably like to spend more time developing that.

And in terms of women’s heels I’m interested in doing some mould making so I can do more unique one off shoes. I guess some of the things I’m interested in learning are less about shoe making and more about other crafts such as woodwork, wood turning, mould making or resin, something which enables me to bring other crafts into my shoemaking work.

What defines a good shoe in your eyes?

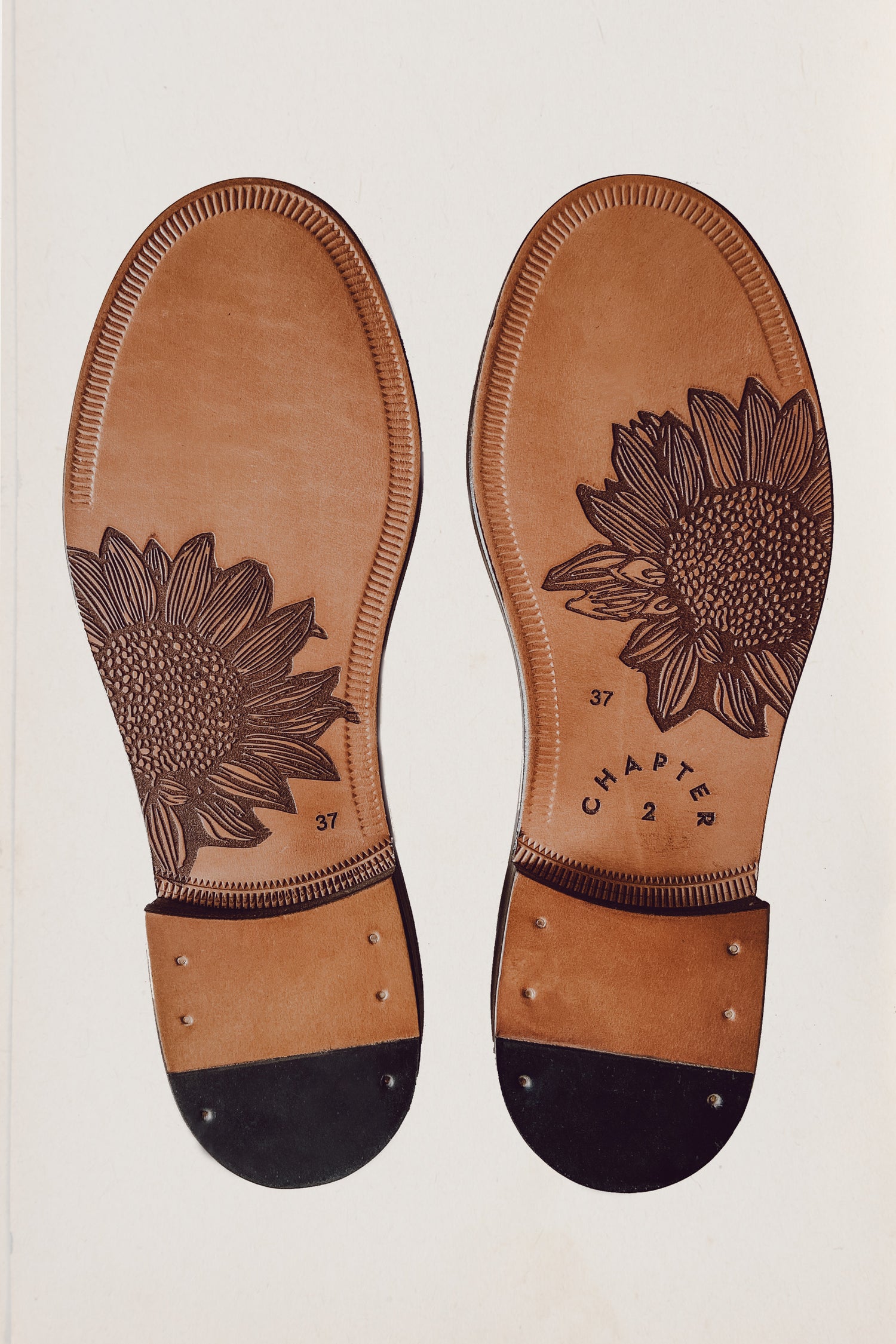

What makes a good shoe: a pair of shoes which can be repaired. That’s also an important part of our CHAPTER 2 boots is that you can repair them. You can take the soles off or have a half sole put on or repair the heel. That’s one of the big problems I’ve got with trainers. I like the look of some trainers but after 6 month they don’t look the same and you can’t repair them in the same way you can repair a pair of leather soled shoes. And I can’t get over that.

For a long time I didn’t wear trainers and then I started to wear them again because they’re comfortable. I started wearing them again when I was living in Brighton, walking up the hill from the station every day to go to my workshop or up to London and they’re comfortable. But I remember one time someone asked me what I did and I told them I was a shoemaker and they looked down and I was wearing pair of New Balance trainers or something and the look of disappointment on their face when they saw me wearing trainers meant I stopped wearing trainers for a long time and only wore shoes.

What are your favourite shoes and do you wear shoes that you’ve made yourself?

I don’t often make shoes for myself. Probably the question I’m asked most when I tell people I’m a shoemaker is did you make those shoes? And the answer is almost always no I didn’t.

I’m lucky that I know lots of other people in the footwear industry and that means I’ve got access to samples or heavily discounted shoes from other brands or I might know where factory shops are. I’ve got loads of shoes, shoes I’ve forgotten I even owned that’s how many I’ve got which is probably a bit much really.

What I often say to people when they’ve asked me if I made my shoes and they look disappointed when I say I didn’t is that no one pays me to make my own shoes. Which is in part a joke and in part true. I haven’t got a lot of extra time to make shoes for myself. There’s lots of shoes I’ve got on a wish list that I’d like to make for myself. I’ve got lasts I’ve made for myself, uppers I’ve made for myself but never turned them into shoes.

The one time I did make a pair for myself I made them on a course and then I also made shoes for my wedding. I made some for me and I made a pair for Fay as well. That felt nice. It was a nice thing to be able to do when we got married. And I’ve made shoes for other people; my mum, my mother and father in law and one other pair of boots for Fay. I’ve got so many shoes I don’t need to make them for myself.

I wear a lot of boots, Trickers boots, maybe 3-4 pairs of Trickers. I bought my first pair in a village hall in Derbyshire. They were a pair of seconds and I bought them for £90 maybe 25 years ago and I’ve still got them and I still wear those ones today. I’ve got the classic Stow boot with various different soles. A rubber sole is good when it’s wet as it is often in the UK. And I’ve got a couple pairs with a leather sole on.

I also wear Redwing Boots, I quite like those, they’re comfortable and they go with the rest of my style and a nice pair of jeans. And in the summer my favourite shoes are a pair of Officine Creative one piece Derbys which I bought from the factory shop in Marche, Italy. I’ve resoled those a couple of times as well. They’re unlined suede so they’re really comfortable.

Let’s answer everyone’s favourite question for the shoemaker: how long does it take to make a pair of handmade shoes?

This is the question I get asked more than any other question if I do a demonstration or an open workshop and I guess it makes sense really why people want to want to know as making things has become so foreign and alien to most people that we can just go into a shop or you can order a pair of shoes online and they just turn up in a box at your house the next day. Most people have no idea what really goes into them, how many processes there are in making a pair of shoes. And then if you if you're doing all those processes by hand the amount of different skills and techniques you have to do or you need to know to make the shoes.

The quick answer is that if I've already worked everything out, so, if I know how everything goes, I've tested the pattern, I've developed it and I've got it ready to go, and if I've just got to cut the shoe out, sew it together, make it and put a sole on, and all of the elements are already pre-fabricated then I could do it in a day. Even when I say that it sounds quite quick, doesn't it?! But I've been doing it for a long time so I suppose I’ve gotten quite fast.

If I'm making the sole from scratch, from a piece of leather and have to put it together that's more time I need to add in. If I also need to develop the patterns and make a last then it becomes days rather than a day.

The thing which really takes a long time or certainly with the kind of shoes I make, which are not always straight forward is the development. Even on CHAPTER 2 boots I lost count of how many samples we made. And if I think back a few years when we made the transition from children's shoes to women's boots, in theory the patterns were kind of already there, the style lines were there but the amount of time it took to develop the women’s boots was huge. It took about a year to get it right and several back and forth as well as a long time to get the last right. So it's really the development which takes the longest time. In shoe making I think that's something people don't always understand. And if you're working with a factory of course they've got other work they're doing so it takes time to make samples. It takes time and effort and money and it can be a really frustrating process. But I've come to accept that it takes it takes a long time.

The difference of how I work is that I can develop a shoe very quickly because I'm doing it all myself. One of the unique or rare things about my shoe making is being able to do all the parts of the process myself. Some people can only do the making, they might get someone else to sew their uppers together and lot of shoemakers have someone else make the last. These are all different skilled processes and most people never learned all of them. Most people are either makers, closers or last makers, one or the other. To be an independent shoe maker I found it helps if I can do more of the processes, then I can have more control of my time lines and I'm not dependent on other people to actually produce the shoes.

When we were making the kid shoes I could last between 8-10 pairs a day using the backpack moulder. It’s a bit of machinery which moulds the back of the shoe. Before I did that it was more like half as many pairs a day. Machines can speed up the process but they're only really cost effective if you're making lots of the same shoe over and over again which most of the time I'm not.

Shoemaking is an endangered craft here in the UK with a small community of craftsmen, which other shoemakers do you admire?

I’m going to give a shout out to a couple of the women in shoemaking, one of my ex-students that I worked closely with on her final collection is Tabitha Ringwood who’s doing lots of exciting women’s constructions and Adele Williamson who is the bespoke maker for Trickers. I really like following her online and watching her develop her craft at Trickers.

I’ve also learnt from lots of different people including my good friend Dominic Casey who’s the first person I ring when I don’t know how to do something or I’m a bit stuck. I’m really lucky to have someone like him as my friend and who I can call on to help me out.

To be honest I really respect anyone who’s making a living out of shoemaking in the UK regardless of what shoes they make or if it’s my aesthetic or not because it’s a really challenging craft and hard to make work as a business. Particularly at a time where people have lost respect for shoemaking because you can buy shoes for £25-£30 on the high street. The cheap prices make people wonder how it’s possible to charge £100s or £1000s for a pair of handmade shoes when you can get shoes for £30 but more importantly we should be asking how is it possible for shoes to cost £30 in a shop? It doesn’t add up and you have to ask who’s being exploited in order to sell a shoe into a shop for that amount?

When I think about shoemaking and sustainability and fashion in general people are starting to become much more interested in who makes their clothes or shoes, where they’re made, the conditions people work in and how the materials are made. So hopefully that interest will be part of keeping the craft alive in this country. There’s lots of people interested in learning shoemaking but the reality is it’s really challenging to make a living as a shoemaker and certainly I do lots of different things in shoemaking to make it work.

What advice would you give to someone looking to get into shoemaking?

If you’re going to go and learn shoemaking have a think about what type of shoes you want to learn to make because it’s not all the same. The principles are the same but the way you do it requires some different techniques. And if you’re going to get someone to teach you or you’re going to take a course have a look at the shoes they actually make on that course and see if that’s the kind of shoe you want to make. If it isn’t try and find someone who makes the kind of shoes you do want to make and see if they’ll teach you how to do it.

Follow people online on instagram as you can watch other makers. In some ways shoemaking is more accessible that it ever has been, even some of the older West End makers who work out of their sheds have instagram accounts so you can really see what they’re doing. There’s also loads of shoemakers working in Japan where you can watch and see some of their work and processes online which is interesting. There’s also upper makers you can see, there’s one excellent upper maker based in Hungary that I enjoy watching some of her techniques.

And then if you’re in the UK go to the Independent Shoemakers Convention, some people do also travel from across Europe and America to go to that too. Buy a shoemaker a drink and they’ll be happy to tell you how they got into shoemaking. They’ve all got their own unique story and most shoemakers spend a lot of time on their own so they’re happy to chat to people about their career and what they do. The Independent Shoemakers Convention is really good for someone young in shoemaking to meet other independent makers, people are very generous in showing skills or giving you tips on where you can get materials or even selling materials or machines. It’s a really good place to go to meet other shoemakers and learn from more experienced makers.

What’s your role at CHAPTER 2 and what’s on the workbench at the moment?

I guess I’m the shoemaker! Now that we’re doing Made to Order I make all the Made to Order boots so that involves clicking the leather (cutting), closing (sewing), lasting the boots and finally attaching our sunflower sole.

When we’re developing new products I often make the first samples so we have lasts here which I’ll tape up and draw patterns on and then make a first sample which we’ll then send off to the factory in Italy. I also check new developments so for example when we made a new sole I’ll make a boot sample so we can attach the prototype and talk to Fay about adjustments before she sends a spec back to the sole makers. I also work on the development of any new lasts and I might trial a new last shape in my workshop. When we made a shoe we went back and forth a few times with the last makers in Italy and in the end it was easier for me to just change the toe shape myself and then send it to them and ask them to produce that one for us.

At the moment on my workbench are a couple of hand painted crust leather samples - special samples of Jackdaw and Wren boot which are nearly ready to share for next months Made to Order.

CHAPTER 2 is just one element of your work, tell us about some of the other shoe making projects you work on?

There are lots of different things within shoemaking that make up a shoemaking career. I’ve taught shoemaking at the Royal College of Art on the MA course, at Cordwainers at LCF on the degree course as well as at Prescott & MacKay. I’ve also taught in Montreal, Canada in the leather school there and I also teach one to one. I generally teach people who work already in the shoe industry so maybe designers who want to have more of an understanding of the shoe making process or people who have done some shoemaking before elsewhere as they’ve already got a certain amount of understanding and want to refine their skills.

And then I do small productions or sample making for other fashion designers. I help people or young designer develop their range to get it to market, small artisan production for shops like Hostem, I make shoes for London or New York Fashion Week. I enjoy sample making for other people. It’s difficult and challenging but it’s interesting as you’re always learning something new.

I’ve also done shoemaking demonstrations at museums which is fun, chatting to people about shoemaking. Open studios are good too as it gives people a chance to see what’s involved. And in a way as a shoemaker I can sit in my studio on my own and not show anyone how it’s done, or I can use social media or open workshops to talk about it. And I suppose in a way if I want people to be more interested I’ve got a bit of a responsibility to educate the public and show them what’s involved in the craft of shoemaking in the hope that they’ll support shoemakers in the future.

You can follow Toms shoemaking on social media @thealchemistsfootprint

Photos: Alun Callender, Leanne Hanna, Fay Murphy, Dion Lee, Atelier Baba, Helen Kirkham, Ancuta Sarca, Ong Oaj Pairam.